One of the great, mutual joys of visiting Chicago was our tour of the Shedd Aquarium. The middle Blandings boy has been an ocean enthusiast since he was about two-and-a-half. A nature lover at heart, he was the one who entered our bedroom at 6 a.m. one day to report, “There’s a bat in my room.” There was. When I asked Mr. Blandings later if he was skeptical of the assessment he gave me a level look and replied, “No. Because it was Ben.”

One of the great, mutual joys of visiting Chicago was our tour of the Shedd Aquarium. The middle Blandings boy has been an ocean enthusiast since he was about two-and-a-half. A nature lover at heart, he was the one who entered our bedroom at 6 a.m. one day to report, “There’s a bat in my room.” There was. When I asked Mr. Blandings later if he was skeptical of the assessment he gave me a level look and replied, “No. Because it was Ben.”

We have been wanting to take him to the Shedd since the mania began, but then number three came along and we looked up and it was five years later.

The creatures I was prepared for. What took my breath away was the architecture. “Are you guys noticing the building?” was a constant refrain during the entire trip, but here I could barely speak.

Design began in 1925 for a world class aquarium. Ernest Graham of Graham, Anderson, Probst & White took the lead on the project. Graham was part of a movement of city leaders to make Chicago, “The Paris of the Prairie.”

Following the World’s Columbian Exhibition in 1839 Beaux Arts architecture became the rage. A marriage of intricate ornamentation and classic design principles, this public space sings its enthusiasm for its mission.

Shells, sea horses, crabs, fish and octopuses adorn door ways, walls and light fixtures.

I cannot think that it is a coincidence that the sea-foam green marble of the dado mimics the ocean.

The intricacy of the design is a marvel. The attention to detail astounding.

I have a friend who did an internship with an architect in high school to meet a graduation requirement. During the interview he asked her, “Do you look at buildings and wonder why they are built the way they are?” Of course she replied affirmatively to get the job, but admitted to me later that she was a fraud.

But I do. Beyond that, I wish I could communicate with those giddy ghosts who haunt these halls, designers who marveled at the freedom to create and the resources that were available to allow them to do so.

Ignorant of how architects work, I have no idea if Graham would have been involved on this level. Who received the job to go back to his drafting table to design the lighting? The thrill of the task would surely have sent me to the ladies’ room to put my head between my knees.

The thing is, this building is a monster, even without the later additions. We are not talking about a couple of clever mosaics in the entry; the wonder is everywhere.

The classic forms of the columns and friezes clearly keep the whole thing from tipping to kitsch.

A project like this in nearly unimaginable today. The Shedd opened just following the stock market crash in 1929.

Over the next couple of years its founders shipped one million gallons of salt water by rail from Florida to accommodate the exhibits.

You can feel them here, those men who committed to making their Midwestern town a destination.

Graham’s firm designed some of the greatest buildings in Chicago including the Field Museum, Union Station, the Museum of Science and Industry, the Civic Opera, the Wrigley Building and the Merchandise Mart.

The Shedd Aquarium was their last.

It was quite a finale.

One of the great, mutual joys of visiting Chicago was our tour of the Shedd Aquarium. The middle Blandings boy has been an ocean enthusiast since he was about two-and-a-half. A nature lover at heart, he was the one who entered our bedroom at 6 a.m. one day to report, “There’s a bat in my room.” There was. When I asked Mr. Blandings later if he was skeptical of the assessment he gave me a level look and replied, “No. Because it was Ben.”

One of the great, mutual joys of visiting Chicago was our tour of the Shedd Aquarium. The middle Blandings boy has been an ocean enthusiast since he was about two-and-a-half. A nature lover at heart, he was the one who entered our bedroom at 6 a.m. one day to report, “There’s a bat in my room.” There was. When I asked Mr. Blandings later if he was skeptical of the assessment he gave me a level look and replied, “No. Because it was Ben.” We have been wanting to take him to the Shedd since the mania began, but then number three came along and we looked up and it was five years later.

We have been wanting to take him to the Shedd since the mania began, but then number three came along and we looked up and it was five years later. The creatures I was prepared for. What took my breath away was the architecture. “Are you guys noticing the building?” was a constant refrain during the entire trip, but here I could barely speak.

The creatures I was prepared for. What took my breath away was the architecture. “Are you guys noticing the building?” was a constant refrain during the entire trip, but here I could barely speak. Following the World’s Columbian Exhibition in 1839 Beaux Arts architecture became the rage. A marriage of intricate ornamentation and classic design principles, this public space sings its enthusiasm for its mission.

Following the World’s Columbian Exhibition in 1839 Beaux Arts architecture became the rage. A marriage of intricate ornamentation and classic design principles, this public space sings its enthusiasm for its mission.

I have a friend who did an internship with an architect in high school to meet a graduation requirement. During the interview he asked her, “Do you look at buildings and wonder why they are built the way they are?” Of course she replied affirmatively to get the job, but admitted to me later that she was a fraud.

I have a friend who did an internship with an architect in high school to meet a graduation requirement. During the interview he asked her, “Do you look at buildings and wonder why they are built the way they are?” Of course she replied affirmatively to get the job, but admitted to me later that she was a fraud. Over the next couple of years its founders shipped one million gallons of salt water by rail from Florida to accommodate the exhibits.

Over the next couple of years its founders shipped one million gallons of salt water by rail from Florida to accommodate the exhibits.

There are moments in your life that you can’t really appreciate at the time. After I had my first child, the corporate environment of the foundation where I was working began to chafe. It got harder and harder to stay there, away from that baby, if I didn’t love it. And I didn’t love it.

There are moments in your life that you can’t really appreciate at the time. After I had my first child, the corporate environment of the foundation where I was working began to chafe. It got harder and harder to stay there, away from that baby, if I didn’t love it. And I didn’t love it.

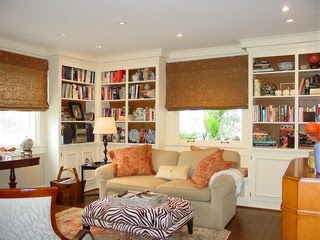

I ran across these pictures this weekend as I was cleaning up some files. Ten years later I look back and wonder what led her to allow me to mess with her nest. Lucky for me she has a high tolerance for risk.

I ran across these pictures this weekend as I was cleaning up some files. Ten years later I look back and wonder what led her to allow me to mess with her nest. Lucky for me she has a high tolerance for risk.